TL;DR

- Daniel Liss, co-founder of Dispo, launches a steelmaking startup, Nemo Industries.

- The idea sparked after a U.S. military war game exposed steel supply chain weaknesses.

- Nemo will build its own pig iron furnaces, using AI to optimize production.

- The startup aims to capitalize on U.S. industrial policy and tax incentives.

- Nemo is in talks for a $100M Series A and has over $1B in state incentives offered.

From Social Apps to Industrial Steel: Liss’ Unexpected Pivot

Daniel Liss, known for co-founding the social media platform Dispo and the AI dating app Teaser AI, has launched an unconventional new venture: a steel startup. The company, named Nemo Industries, has been operating in stealth mode, but is now stepping into the public eye with an ambitious plan.

The inspiration for this pivot came after Liss wrote a series of op-eds for TechCrunch on antitrust regulation in the tech sector, which led to his participation in a military strategy simulation at the National War College. The war game scenario focused on a hypothetical U.S.-China conflict over Taiwan and the South China Sea—revealing critical gaps in the U.S. defense manufacturing base.

“If we did have ship-building capacity, we don’t have the steel to make it,” Liss said.

This realization ignited what he calls an obsession with the U.S. steel supply chain, leading to the founding of Nemo Industries.

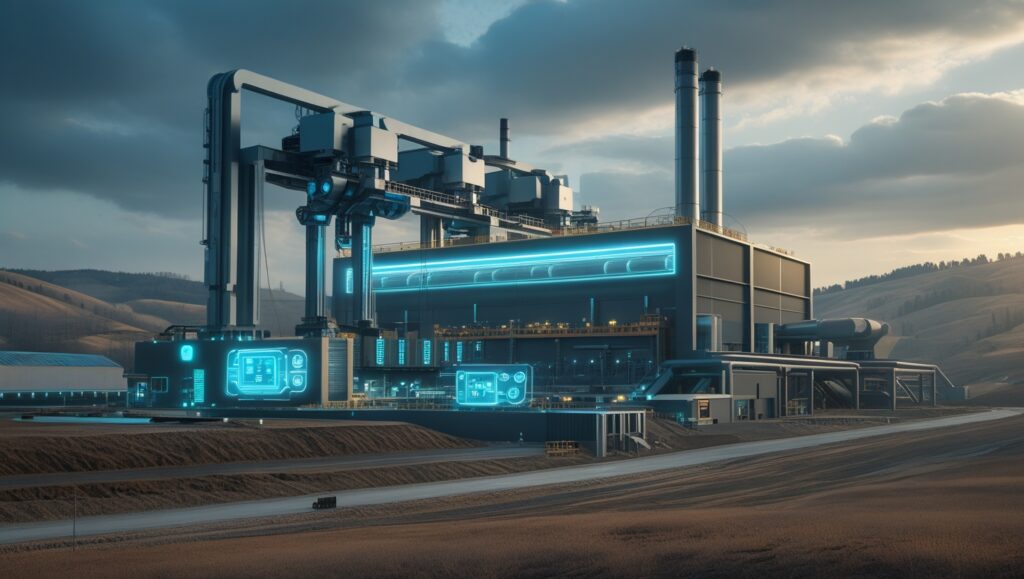

Nemo Industries: Steel and AI in One Furnace

Unlike typical industrial tech startups, Nemo isn’t just selling software — it plans to build its own pig iron furnaces from the ground up. Liss believes that AI-native operations from day one could yield a 20–30% margin advantage compared to legacy players in the steel sector.

“These plants are run on, at best, Excel. At worst, clipboard technology,” Liss said.

The company will apply AI not only to operational efficiencies but also to energy use. Nemo’s furnaces will be powered by natural gas, which emits significantly less CO₂ than traditional coal-fired steelmaking. Liss also noted the company is exploring carbon capture, citing incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act as a profitability lever.

Capital, Partners, and Geopolitical Tailwinds

To scale its vision, Nemo has already raised $28.2 million in seed funding and is currently in talks to raise a $100 million Series A, according to PitchBook. Two southern U.S. states have also offered over $1 billion in incentives—contingent on Nemo building three plants over 15 years.

Backing Liss is Michael DuBose, a former executive at Cheniere Energy, known for his work in LNG infrastructure. This partnership reinforces the venture’s credibility in large-scale industrial projects.

Why Venture Capital Is Paying Attention

Though unconventional, Nemo fits a pattern of VC interest in foundational infrastructure. Recent moves by Hyundai Motor Group—who are investing $6 billion in a new U.S. steel facility—demonstrate rising urgency around domestic production.

Liss argues that this type of industrial renaissance could yield outsize returns, akin to historical successes in oil, steel, and rail.

“The Rockefellers, Carnegies, and Fricks were in these categories for a reason.”

Industry Snapshot: U.S. Steelmaking & Investment

| Metric | Value | Source |

| U.S. steel output (2024) | 87 million metric tons | Statista |

| Projected U.S. steel demand (2030) | 110 million metric tons | World Steel Association |

| Hyundai U.S. plant investment | $6 billion | Reuters |

| Nemo Industries’ seed funding | $28.2 million | PitchBook |

| Potential state incentives to Nemo | $1 billion+ (over 15 years) | TechCrunch |

The Strategic Bet on Domestic Industry

At a time when geopolitical tensions are increasing and U.S. policymakers are pushing to onshore critical supply chains, Nemo Industries appears to be well-timed. With its combination of AI innovation, cleaner energy inputs, and American industrial scale, the startup could represent a new generation of “deep tech” manufacturing companies.

Liss’ career leap may seem drastic, but it aligns with a broader trend: Silicon Valley is waking up to the value—and necessity—of investing in physical industries once deemed too old-school for tech disruption.